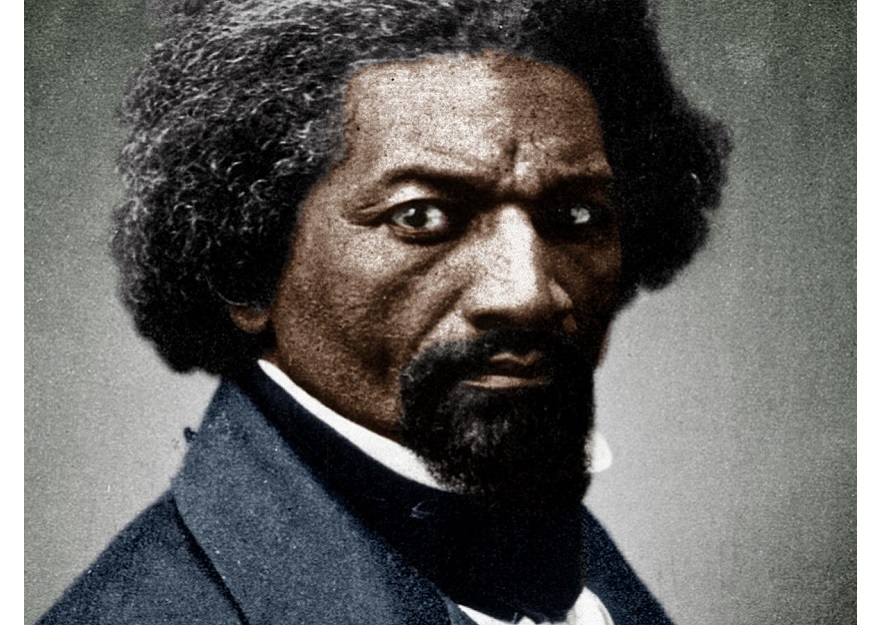

Frederick Douglass, a well-known abolitionist and preacher known for his mastery of language and prose, remains a prominent figure in the annals of history for his longstanding battle against the practice of slavery in America. Prior to his campaign against slavery and his fight for African American equality, Douglass was in bondage. He was enslaved for the first 20 years of his life.

Born into slavery on the east coast of Maryland in 1818, Douglass was enslaved by several people, but perhaps Captain Thomas Auld was the one who made his life miserable. Auld was the son of a commander in the American army. As a Christian and well-known local shipbuilder, Auld inherited enslaved people through his first wife, Lucretia.

Soon he became a cruel slaveholder who beat and starved his enslaved workers while preventing them from reading and writing or from gathering to worship. Describing his moments with Auld as some of the saddest experiences of his slave life, Douglass wrote in an autobiography that Auld “submitted me to his will, took possession of my body and soul, reduced me to a possession, reduced me as a well-known slave breaker, the how an animal should be processed and whipped for submission … “

After Douglass was leased to other slave owners, Douglass returned to Auld in 1838. That year, after meeting and falling in love with a free black woman named Anna Murray, Douglass devised an escape plan. On September 3, 1838, Douglass, with Murray’s help, hopped north aboard a railroad, disguised as a free black seaman.

He fled to the free north and ended up with Murray in Rochester, New York. As a free man, Douglass became deeply involved in the abolition movement, which led him to travel widely to give speeches, including two years in Europe from 1845 to 1847. He began publishing his own abolitionist newspaper, The North Star, and drew with prominent abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison. People flocked to the venues only to hear Douglass speak.

Auld had become aware of Douglass’ achievements as an abolitionist and famous statesman by this time, but he did not meet him until 1877. Auld, 81 that year, was very ill. Wanting to make peace with his past, he asked his servant to invite Douglass to visit him at his house.

It was an emotional moment when Douglass arrived at Auld’s house on the east coast of Chesapeake Bay. Douglass said in his last autobiography that he remembers “hold” [Auld’s] Hand ”and“ friendly conversation ”. Douglass then served as the US Marshal for the District of Columbia. He said in his autobiography that Auld addressed him as “Marshal Douglass” but he was quick to correct him and said, “Not Marshal, but Frederick to you, as before.”

Auld couldn’t stop crying after hearing these words, Douglass wrote, adding that “The sight of the circumstances of his condition touched me deeply and for a while stifled my voice and left me speechless.”

Douglass further asked Auld what he thought of his escape from slavery decades ago. “Frederick,” said Auld, “I always knew you were too smart to be a slave. If I had been in your place, I would have done it like you did. “

“I didn’t run away from you,” Douglass replied. “I ran away from slavery.”

Aside from the fact that the meeting was a “victory round for Douglass”, he would have hoped that Auld would have better understand his family roots at their meeting. In fact, Douglass reconciled with Auld and the two separated as friends, but that didn’t mean he reconciled himself to slavery.

“Any interpretation of this encounter that says blacks must suck it up and whites must forgive to have peace totally misses the mark,” National Geographic quoted Noelle Trent, director of collections and education at the National Civil Rights Museum, quoted. “This is not a lesson in forgiveness. This is a lesson in personal reconciliation. “

Indeed, Douglass never shied away from publicly criticizing Auld for his treatment, but he always added that he never “meant to wrong him”.

“I have no malice towards you,” wrote Douglass in an emotional open letter to Auld in 1848. “There is no roof under which you are safer than mine, and in my house there is nothing you can take for your comfort that I would not readily grant … I am your fellow man, but not your slave.”