The 245th birthday of the United States of America is cause for celebration, soul searching and scarring, including the violation of the January 6th attack on the Capitol. What was it about? How should we remember this trauma?

At the point where the storm on the Capitol had reached its symbolic climax, US President Biden began his first joint address to Congress by describing the January 6 events as “the worst attack on our democracy since the Civil War.”

I leave it to historians to determine whether the Jim Crow laws, the internment of Japanese Americans, McCarthyism, the disenfranchisement of the sexes, and the repression of racist voters weren’t worse. Instead, I ask: Was the storming of the Capitol an attack on democracy?

To my friends, my liberals, the question is ridiculous; for many quite offensive, since the attack was a sacrilege, “the joyful desecration of this, our temple of American democracy”. Maybe. But the actual search for souls requires doubts, the question of whether and where we, not just others, have gone wrong.

Great Seal of France

Source: Wikimedia Commons

I ask myself: Was January 6th not only an attack on democracy, but also by it?

A telling sign has stood in the heart of the Capitol for more than two centuries – and behind Biden when he addressed Congress. When the French stormed the Bastille in 1789, the House of Representatives took over the fascio and made it the second most important symbol of the house and arguably the country.

But while the fascio represents (a certain reading of) democracy, it flies in the face of liberalism. This tied bundle of rods was not a new invention. It fascinated the Roman political imagination – and inspired Italian fascism heralded by Mussolini’s March on Rome in 1922. In contrast to the National Socialist appropriation of the traditional, good-natured swastika (Sanskrit for “promote well-being”), the fascio visually manifests its credo: The once unique and living rods are now dried, cut and formed into a unified unit that forcibly holds an ax. An anti-individual symbol, if there ever was one. And a strong collectivist symbol.

No wonder both the French and American revolutions turned to the fascio. After the Revolution of 1789, the First French Republic changed the country’s official Great Seal, removing the monarchy’s insignia and replacing Marianne, the goddess of freedom and reason, and the inspiration for the Statue of Liberty. The most visible symbol of the seal is held in Marianne’s right hand: the fascio.

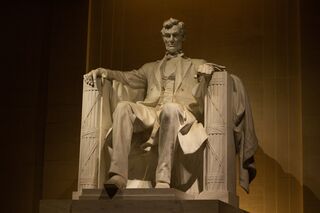

Fascio at the Lincoln Memorial

Source: CC0 Public Domain

In the 1920s and 1930s, politicians and architects who were aware of the rise of fascism, including its symbolism, were often very fond of it as an antidote to communism. After crossing the Atlantic, the fascio spread over the entire United States. In NYC, where George Washington was sworn in as the first president, his statue stands and his cloak covers the fascio. The Abraham Lincoln Memorial in Washington DC shows the leader on a fascio-made seat. Next, as mentioned, in the House of Representatives, huge fascio axes adorn the wall behind the loudspeaker, on either side of the US flag.

Ashamed of the people who desecrated the Capitol, the Liberals missed what has desecrated this temple all along in its very sacred heart.

United States House of Representatives Washington

Source: US House of Representatives Washington

The fascio introduces what I call the “liberal uncanny”. For the French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, following Freud, “the uncanny” is the unsettling feeling of experiencing something strangely familiar that “puts people in a field in which we do not know how to distinguish between good and bad”. This confusion underpins current liberalism and its ambivalent approach to what the fascio most represents: the people, this political human collective that is greater than the sum of its parts.

On the one hand, democracy, literally “the rule of the people”, is justified by the latter. Democracy is ultimately by, by, and for the people who actually made the great modern democratic revolutions: the Americans and the French.

We the people

Source: Getty Images / iStockphoto

On the other hand, many rightly sense something very uncanny about “the people”. It conveys populism and the mob mentality, the collective unleashing of the stubborn id from its civilizational constraints and probably culminates in the bloodbath of ultra-nationalism, fascism, Nazism and communism of the 20th century. And it inspired Trump’s rhetoric and the actions of his followers.

Can we have this cake and eat it too, maintain popular power without paying a price?