By Bill Donahue

It’s a Friday morning in May, and it’s sunny in central Maine, and the grass is green. The drab gray hues of mud season have ony recently exited the north country, and it is at last that time of year when you might expect to see a Frisbee or two lofting high over the main campus of Unity College, which sits 20 miles northeast of Waterville, outside the town of Unity. It’s on mornings like this that faculty members like to host class outside, so that students can discuss, say, Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring amid the chitter of birds.

But today, there is not a single student on the Unity campus. Even as the majority of Maine colleges and universities navigate COVID to host some in-person classes — including some with modest resources, like Thomas College and Husson University — Unity is off-limits to all but invited visitors. When one 1997 graduate, Hauns Bassett, recently brought his kids to campus to ride bikes on the school’s long, sloping drives, security officers asked him to leave. Bassett says they told him they’d booted other visitors too, foragers who’d come to pick edible mushrooms and to harvest dropped apples in the college’s small orchard.

“They asked them to leave!” Bassett says, aggrieved. “That is so un-Unity!”

Certainly, it is not of a piece with the school’s boots-in-the-soil reputation. Founded in 1965 on land donated by a local chicken farmer, Unity has always championed experiential learning, so that students crouched in the mud to plant rutabagas and ventured into dark forests to count tree rings for dendrology class before moving on to careers as game wardens, foresters, and fisheries biologists. Never an academic powerhouse, Unity has long called itself “America’s Environmental College” and appealed most to restless students more eager to get their knees dirty than to parse the meter of Shakespearean sonnets. As such, its student body is known for commingling farm kids and flower children, tree huggers and tree harvesters. The Unity Woodsmen team is often thick with virtuoso axe throwers. And a certain backwoods conviviality has always been part of the college’s brand. In 2007, when a beloved maintenance worker retired after 25 years’ service, more than 150 Unity students marked his last day by walking two-and-a-half miles to work with him.

In recent years, Unity has boasted as many as 700 in-person students. This morning, though, the dorms are locked. The much-loved Mongolian grill in the school cafeteria is cold to the touch. But as I stroll the deserted lawns, I’m aware of a certain amperage emanating from the second floor of Founders Hall North, a long, white-clapboard building that was, long ago, a chicken barn.

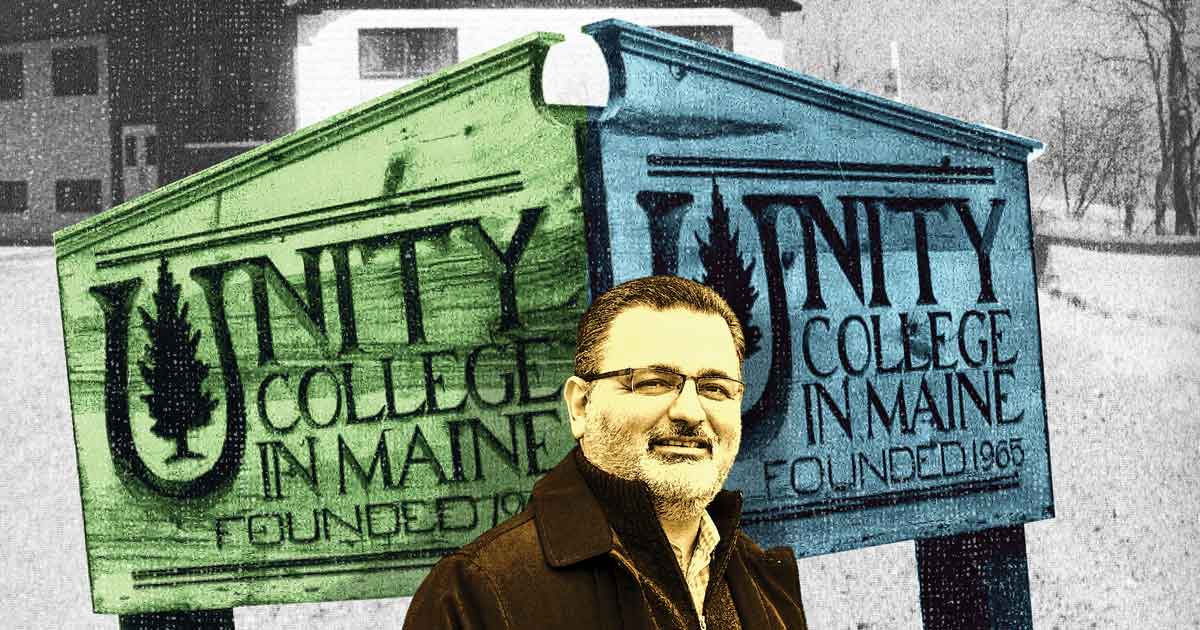

Unity’s 11th president, Dr. Melik Peter Khoury, is up there reinventing the college. Since being promoted from his vice-president post in 2015, Khoury has overseen a shift in the ratio of full-time faculty to part-time adjuncts, embracing adjunct-driven online learning to the point that each four-year student is now obliged to complete all general education classes, about a third of the credits required for graduation, in a virtual environment. The hybrid-learning course catalog still offers plenty of in-person courses, but if they’d prefer, students can now choose to take all of their courses online. And last August 3, at 9 a.m., Khoury delivered perhaps the most significant blow to in-person learning when the college laid off 13 full-time professors in a single dispatch of emails — either half or one-third of the full-time faculty, depending whose numbers you trust. As of noon that day, the emails pronounced, each recipient was “no longer an employee of Unity College.” If dismissed professors wished to clear out their offices, the notices informed them, they’d need to contact campus security.

Concurrently, the president scrapped the college’s semester system: all Unity classes are now five-week intensives, and there are not two, but eight, terms a year. A corporate vibe has descended upon the college. Khoury, who identifies as both president and CEO, has divided the college into what he calls “sustainable educational business units.” Meanwhile, Unity has expanded geographically. During Khoury’s tenure, the college has set up classrooms at a guest lodge in Jackman and also at New Gloucester’s Pineland Farms, a former “school for the feeble-minded” and now a mixed-use campus, where Unity will offer non-baccalaureate degrees starting this fall to aspiring vet techs and solar techs, among others — a first for the liberal-arts college.

According to Khoury, the changes have helped boost enrollment to some 1,600 full-time-equivalent students. What’s more, Khoury says, the percentage of minority students enrolled has more than doubled since 2012. And yet, many students, alumni, and former faculty members are frothing with discontent. Following the dismissals last August, 61 of them signed a letter to Khoury demanding he resign, alleging that he was “determined to destroy” the college. This spring, when a few alums administered a very unscientific online poll of 145 alumni, ex-professors, and neighbors around town, Khoury notched a 98.6 percent disapproval rating.

Khoury is hardly trying to broker a peace with his critics. Soon after I climb the stairs of the old chicken barn to meet him, he sounds a note of indifference about the fate of on-campus learning at Unity. “We’re in the education business, not the hospitality business,” he tells me. “We don’t have to be a country club with books.” Later, he pokes fun at what he calls the “ed-u-ma-cated” elite. And while Unity has announced its intent to reopen classrooms and residence halls in August, Khoury says that the long-term fate of in-person learning isn’t his to determine. “That,” he says, “will be decided by the students.”

Khoury, who is 48, was born in Sierra Leone to a Lebanese father and an English mother. He spent his childhood in the tiny West African nation The Gambia, waiting tables and washing dishes at his parents’ small seaside restaurant. He entered the University of Maine at Fort Kent in 1995, where he distinguished himself as an All-American goalkeeper on the school’s flourishing soccer team before earning an MBA in Orono, then a doctorate in business administration. A practical bent has always guided him (he calls himself a “student of organizational design”), and he carries a certain intensity. Even though he’s slightly thick in the middle these days, he still has a hungry, agile manner, as though he could readily dive after a kicked ball. There’s a muscular swagger to him, and he places a high value on improvisation.

“We should consider how the music industry has evolved,” he tells me, as we discuss distance learning. “There was a time when you could only listen to music live, in person. But then records came along. Then there were cassettes and CDs and then streaming. What would it be like if we said, ‘No, the only way you can experience The Beatles is if you fly to Liverpool and watch them in person?’ We are confusing the vehicle of education with education,” he says, fixing me with his eyes, “and we can’t afford to do that.”

Khoury’s battle cry comes at a moment of severe crisis for higher education. With tuition costs skyrocketing and student debts mounting, college enrollment has been steadily decreasing for a decade. In February, a Department of Labor report revealed that, over the preceding 12 months, amid COVID, colleges and universities nationwide cut 650,000 jobs, a 13 percent workforce reduction. The residential model of higher ed is especially imperiled. Tuition and room and board at many colleges now tops $70,000 a year, thanks in part to students’ growing taste for luxury dorms and state-of-the-art squash courts.

Only top-tier schools with deep endowments are still able to provide enough scholarship money to lure students of modest means. Harvard can do it, certainly, with its $40 billion endowment, and Maine’s most selective schools — Bowdoin, Bates, and Colby — seem likely to weather the storm for the foreseeable future. But across the country are hundreds of impoverished small private schools that are, like Unity, little known outside their region and possessed of unimpressive endowments akin to Unity’s $18 million nest egg. More than two dozen such colleges have closed nationwide since 2018, and of the 1,000 or so that remain, some 20 percent are on the verge of going under, according to a recent evaluation by a University of Pennsylvania analyst.

Throughout the decades, Unity College has developed a reputation for taking a hands-on approach to the study of agriculture, forestry, wildlife management, and other environmental disciplines. Left to right: in the Heritage Livestock Barn, on Unity’s campus; deer dissection; a herpetology class, held in the woods. Courtesy of Cheryl Frederick, Juliana Kakubson Doggart, Lily Glynos, respectively.

Online pedagogy is an increasingly popular adaptation. Even before COVID, the stigma surrounding virtual teaching had faded enough for elite schools such as MIT and Stanford to offer distance learning, and to Khoury, the virtual classroom holds a magical, egalitarian appeal. “A 42-year- old mother working in Chicago deserves to experience Unity’s programs without having to quit her job and move here,” he says. “Why can’t she take classes online?” Unity offers online courses at $470 per credit and $550 for in-person learning — both costs more on par with public institutions than private ones.

Khoury earned his own doctorate online, through the University of Phoenix, in 2011, and he takes pride in being an early adapter. “In education,” he explains, “you’ve got to be where the puck is going to be. You’ve got to be nimble. People who are guessing where higher education is going to end up five years from now, they’re taking a huge gamble.”

Could the future find Unity offering no in-person instruction at all? That prospect alarmed many in the Unity orbit last year when the college’s board of trustees authorized Khoury to explore the sale of the main campus. The property has never been listed for sale, however, and when I ask about the possibility of an all-remote future, Khoury seems irked. “Show me a document that says we are not doing face-to-face classes,” he demands.

Later, however, he suggests that the future is out of his hands. “If there is not a critical mass of students,” he asks, “what are our options?”

It’s Saturday morning now, gray and cold, and I’m a few miles east of Unity, at a hilltop farmhouse in Thorndike, sitting at a long wooden table and looking out at gathering rain clouds as two former Unity College professors, both fired last August, seethe over Khoury’s vision for the college.

“I don’t believe for a moment there’s going to be a full hybrid-learning model,” says Aimee Phillippi, a biologist who taught at Unity for 17 years. Phillippi thinks Khoury won’t gather enough students to the Unity campus. Indeed, in a letter to students in June, Unity’s vice president of hybrid learning wrote that in-person courses would be limited for the term beginning in August. To fully reopen campus, the letter said, “we need a critical mass of 350 students in residence. We are below that threshold.”

“No student with any sense would pay for a hybrid education when they’re required to take all their gen ed classes online,” Phillippi says.

“When Melik wanted to be president, he’d be around the soccer fields, playing with the students,” says Janis Balda, a lawyer who taught business at Unity and is now treating us to doughnuts and tea in her home. “Then, after he became president, he never did it again. He’s a chameleon.” Balda pauses, considering Khoury’s immigration story as she tries to be empathetic. “But when you’re coming from another culture,” she adds, “you have to be a chameleon.”

Conflict between faculty and administrations is all but endemic to higher ed, but both professors depict Khoury as a once-in-a-lifetime disaster. Phillippi keeps calling last August’s dismissals “the Great Purge,” and she complains that cost-cutting was more important to Khoury than quality teaching. When he was promoting the school, she says, “He never even talked about our achievements.”

“We are confusing the vehicle of education with education,” Khoury says, fixing me with his eyes, “and we can’t afford to do that.”

For many critics of the school’s new direction, nostalgia mixes with bitterness. “Unity was a family,” Hauns Bassett says. “If you skipped a class, the professor would track your ass down. She’d go looking for you in your residence hall. It was the ladies who worked in the kitchen. It was public safety — those guys were nice to you, even if they had to write you up for doing some stupid college-kid thing. It was [biology professor] Dave Knupp. You never knew what kind of roadkill Dave was going to bring to school in a Shaw’s bag to cut up with his pocket knife.”

In 2017, taking guidance from Khoury, Unity’s Board of Trustees stripped voting privileges from its faculty and undergraduate representatives. (Alumni’s voting powers had been cut off years earlier.) At the same time, the board broadened Khoury’s power to set the agenda at board meetings, adding a clause to the bylaws that read, “All issues, proposals, initiatives, inquiries and resolutions being proposed to the board by persons other than voting members of the board must be reviewed and approved by the president.”

Kathleen Dunckel, who taught forest science and GIS at Unity from 2009 to 2020, was the board’s faculty representative when the bylaws were changed. She quit the board in protest, frustrated with its increasing deference to Khoury as decision maker. “I sat with him in his office countless times trying to tell him that when you have a roomful of PhDs asking questions, that means that they’re engaged and they care,” she says. “I told him that Unity is based on a model of community-based decisions, and he said, ‘But that takes too long.’” Khoury doesn’t deny the exchange. Amid higher-ed’s financial crunch, he later tells me, “institutional leadership has had to change the way it operates.”

Sitting in Thorndike, nibbling my doughnut, I feel like I’ve ventured into a war zone where each side harbors its own truths.

“Melik raised his voice frequently, even at faculty meetings,” says Phillippi, one of three former faculty members to tell me this. “Once, a student of mine walked by a meeting and heard him swearing. He was concerned.”

“He came here to make a name for himself,” Balda says, again thinking of Khoury’s immigration to Maine, “and then to not be celebrated when he felt he deserved respect for his title and position?” Balda suggests that, because he felt disrespected, Khoury disengaged from the faculty and remained a stranger. “What’s the real authentic Melik?” she asks. “People don’t even know who he is.”

“I am a first-generation American from humble beginnings who got the gift of higher education,” Khoury tells me, summing up his life story during one of two 90-minute interviews, “and I’m in a position to figure out a way to make that more accessible. I’m scared of a world that is uneducated.”

He learned to appreciate education and worldliness as a kid, he says, growing up in The Gambia’s largest city, Serekunda, which attracted a wide array of international visitors. “People from all different religions and cultures mixed in a very natural way,” he says. “It was kind of like what I thought America was.”

Late at night, after the family restaurant closed, Khoury and his parents often watched an American TV show, M*A*S*H, about the Korean War. The show’s star character, Hawkeye Pierce, an Army surgeon, wrote letters to his family back home in the fictional town of Crabapple Cove, Maine. When Khoury began looking at American colleges, he focused on small towns in Maine, like Fort Kent, imagining Crabapple Cove. In his mind’s eye, the place was “beautiful and pristine.”

He emigrated, then continued to work just as he had in the restaurant, with vigor and a penchant for multitasking. As an undergrad, he had a work-study job in the school library and also stocked shelves at a grocery store. “I’ve worked for everything I have,” he says, “and I believe in giving back.”

I admire Khoury’s conviction, but our talks carry an edge. At one point, I mention that I graduated from Colby. Soon, he begins referencing my alma mater in ways that seem to suggest I’m unfit to gauge Unity’s financial predicament. “Colby spent $10 million on COVID preparedness,” he notes. “I wish I could do that.” Then, as we tour a newish science lab on the Unity campus, he says, “But you went to Colby. This is probably nothing to you.”

Left to right: in the Heritage Livestock Barn, on Unity’s campus; working with Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife officials at biological check stations during moose seasons; the Unity Woodsmen team, in the late ’80s. Courtesy of Cheryl Frederick, Juliana Kakubson Doggart, and Tammie DeGrasse Stammers, respectively.

Later, when I ask about his alleged yelling and swearing in faculty meetings, the conversation turns heated. “That almost sounds racist,” Khoury says. “I am a brown man who is passionate. You see me. I move my hands when I talk.” He gestures for effect. “What happened to the inclusive society that welcomes all?” he asks. “I am not a privileged, passive-aggressive, mild-mannered gaslighter. I am honest. I am different, and sometimes people’s differences are not welcome.”

Tentatively, I begin to ask whether modes of expression are different — more animated, perhaps — where he grew up, or among the Lebanese of West Africa. Khoury cuts me off.

“I’m not Lebanese,” he says. “Have you seen my birth certificate? I’m a naturalized American. Would you ask that question of a white man?”

Unity’s director of media relations, Joseph Hegarty, is monitoring the interview and gingerly breaks in. “You have to let him ask the question,” he says to Khoury. “He hasn’t even gotten to the question.”

“You’re ascribing a bias towards me,” Khoury continues. “I know I’m not welcome in your country.”

“He’s not saying that at all,” Hegarty replies.

“He went after my ethnicity,” Khoury says.

Before long, Khoury apologizes. “I tried to get into the minds of others, and that was wrong of me,” he says. But now, I’m hesitant to ask anything more about his upbringing. The subject feels too volatile, and I’m beginning to realize that specific details — the name of his high school, say — aren’t critical, because I glimpsed the soul of the story days earlier, while reading the acknowledgements section of Khoury’s doctoral thesis.

“To my brother Salah, my sisters Shadia and Souad,” he wrote, “and my mother Amal, a special thank you for supporting my decision to break from the family tradition and get a formal education, even though they did not understand why. My family’s blind support and pride in something they did not value, simply because it was my journey, is the reason I hope to use my doctorate to facilitate access and support to any student who dares to dream and make a better life through higher education.”

Khoury comes from a world so far from the vaunted halls of New England academe that quite possibly no one there will ever understand exactly who he is. He’s an outsider. It’s what makes him determined and innovative. It’s also, I suspect, what makes him defensive and prickly. And it seems possible, too, that his status as a mysterious outsider might make some of his critics a bit anxious.

After my second long talk with Khoury, I step into the hallway to meet David Bass-Clark, and the charged atmosphere instantly lifts. Hired last year, Clark is the 34-year-old director of virtual-and-augmented-reality development for Unity’s distance education program. He oversees a small team of part-time contractors developing video-game-like learning tools for online classes, and he’s exuberant and chummy and inclined to flop his long, skinny arms about, gesticulating.

“I’m so excited to be with a school that values innovation,” he says, noting that Unity is one of a handful of colleges nationwide to have a department specifically dedicated to VR and AR. “We’re democratizing access. We’re enabling students to do things they can’t do in reality. We’re giving them the ability to fly and to rescale themselves.”

Bass-Clark shows me a VR simulation he developed to help students learn how to do whale surveys. On a conference-room screen, suddenly, is a cartoon ocean speckled with gushing whale spouts. The challenge involves counting the spouts and estimating their distance from a virtual boat. “You can do things faster and cheaper and without danger online,” Bass-Clark tells me. Whenever I ask him something, he bathes me in affirmation. “That’s a really good question!” he says.

What’s not to like about Bass-Clark? I love his energy, and he embodies the forward-looking, inclusive spirit that Khoury is bringing to Unity. Still, I’m with him when he says that virtual learning “is not a panacea.” I’m sitting in a darkened conference room, watching pixelated animals on a screen as real birds flitter away in the branches outside. There’s a joy out there in real life, an infinitude of possibilities that can never be duplicated on a screen, and I’m sad that, going forward, Unity students likely have fewer opportunities to get dirt on their knees. The school is becoming more accessible, certainly, but something essential will be lost.

The rancor surrounding Unity won’t help the college either, and right before I climb into my car to drive home, Khoury pulls me aside, imploringly, to hone in on this strife. “I know time is money,” he says, “but just a couple of minutes.”

We step into his office, where he argues that life at Unity College has been fraught almost since the 1970s. “We have a history of running presidents out of town,” he says, a claim that others would dispute. “I didn’t run.”

As Khoury sees it, he will in time transcend the school’s history to create a new college where life is calm and equitable. He isn’t there yet, and he assures me that for a while at least, strife will continue at Unity. Invoking the cool, abstract patois of organizational theory, he says of the college’s overhaul, “This is a real interesting exercise in change management, and with change management you’ve got current state, you’ve got desired state, and” — he fixes me with his eyes one last time — “you’ve got chaos in the middle. And that’s where we are right now, in chaos.”

A “FRANKLY IDEALISTIC” HISTORY

For a school founded on a shoestring on a poultry farm, the Unity Institute of Liberal Arts and Sciences, as it was first known, launched with lofty ambitions. “Unity is frankly idealistic,” declared the first course catalog, in 1966. Admissions, it explained, would have less to do with a student’s academic record than with “his willingness to face himself.” Faculty would comprise “men and women who feel that teaching is an art . . . who recognize that there is more — much more — to education than what goes on in the classroom.”

Noble rhetoric for a group of founding businesspeople who considered opening a bowling alley or sock factory before settling on a college. Many of Unity’s original trustees, led by Bert Clifford, a dairy farmer turned telecom pioneer, were motivated by the threat of rural decay as the poultry industry faltered. The college, at first, was a knockabout affair: the power company sometimes shut the lights off, founders butted heads with faculty over direction, rural Mainers and urban draft dodgers eyed each other warily in class.

Unity didn’t embrace its environmental mission until the ’70s, but when it did, it went all in. “Underlying everything Unity does is the theme of human ecology,” the 1977 catalog explained. “You cannot truly know yourself until you develop your personal relationship with your world.” Still, relatively few answered the call, and financial troubles dogged the college until enrollment and fundraising swelled in the later ’90s.

More recently, Unity’s close-to-the-land brand has earned it national attention. The media ate up an annual fishing derby in the ’00s in which students hooked fish tagged with scholarship vouchers. In 2012, Unity became the first U.S. college to divest fossil-fuel producers from its endowment. The year before, it christened the country’s first dorm built to passive-house efficiency standards, a roughly half-million-dollar investment, largely grant funded, and a long way from the poultry farm. — BRIAN KEVIN

BUY THIS ISSUE