Instead Douglass, at age 20, found in New Bedford a busy modern port, one of the wealthiest cities in the United States. Many whales had been killed to fund the patrician houses and opulent gardens. By September the horse chestnuts would have lost their candelabras of pink flowers, their leaves turning yellow amid avenues of reddening maples, but gardens were still lush with flowers. The young fugitive found the scene peaceful in contrast to the violence and squalor he had known in Maryland. That afternoon, as he strolled the bustling wharf, he saw no laborer — white or Black — whipped or cursed by an overseer. He would come to learn that this was no Eden, but on that first day it seemed like one.

In one of the most audacious adventures in American history, Douglass had escaped from slavery on September 3, after two failed attempts that had resulted in a 15-mile forced march and jail. The woman now beside him — Anna Murray Douglass, five years his senior — had encouraged his third plan. She even bought his train ticket by selling her feather bed. They were born 3 miles apart and had played on the same bank of the Tuckahoe River in Talbot County, later laboring near each other in Baltimore. But thanks to her birth shortly after her mother’s manumission, Anna was free, unlike most of her siblings.

Douglass had always been told that his father — the man who kept Douglass’s mother enslaved, he assumed — was white. Southern legislators had carefully arranged that children occupied the social status of their mother, while permitting a father to torture or sell his own offspring.

Although dark-skinned himself, a free sailor had generously lent Douglass his identifying papers, which bore an official-looking image of a bald eagle that Douglass hoped would distract from closer scrutiny of his description contained in the papers. (Photography was in its infancy.) It worked.

Dressed in sailor garb, he settled in the “colored” car. With his back and memory scarred by the horrors he had felt and witnessed, Douglass tried to convincingly use maritime terms he had picked up in a shipyard as he learned hull-caulking in Baltimore.

Upon arrival in New York, he wrote to his future wife. Despite what he described as his “homeless, houseless, and helpless condition,” she immediately traveled northward to join the fugitive who might at any moment be recaptured by slave-hunters. Her devotion played a central role in Douglass’s escape out of bondage and into history.

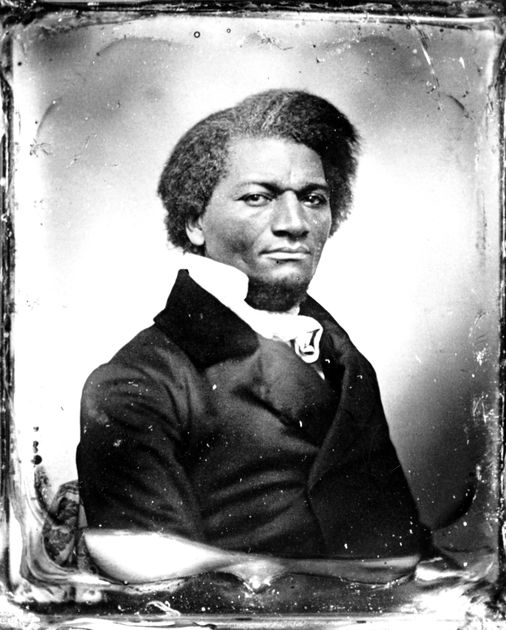

Unshackled, Douglass would rise to abolitionist orator and writer, adviser to and public critic of President Lincoln, and ambassador to Haiti. He was one of the first prominent American men to support women’s suffrage. Dedicated to the struggle to get the United States to live up to its own founding documents, he published his own abolitionist newspaper. “Douglass was a man of words; spoken and written language was the only major weapon of protest, persuasion, or power that he ever possessed,” wrote Yale historian David Blight, who won a Pulitzer Prize for his 2018 biography, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom. “There is no greater voice” on America’s journey from slavery to freedom, Blight wrote, “than Douglass’s.”

In Massachusetts, he found this voice.

A 19th-century illustration of Douglass and his wife, Anna Murray Douglass, arriving in New Bedford in 1838.from wikisource

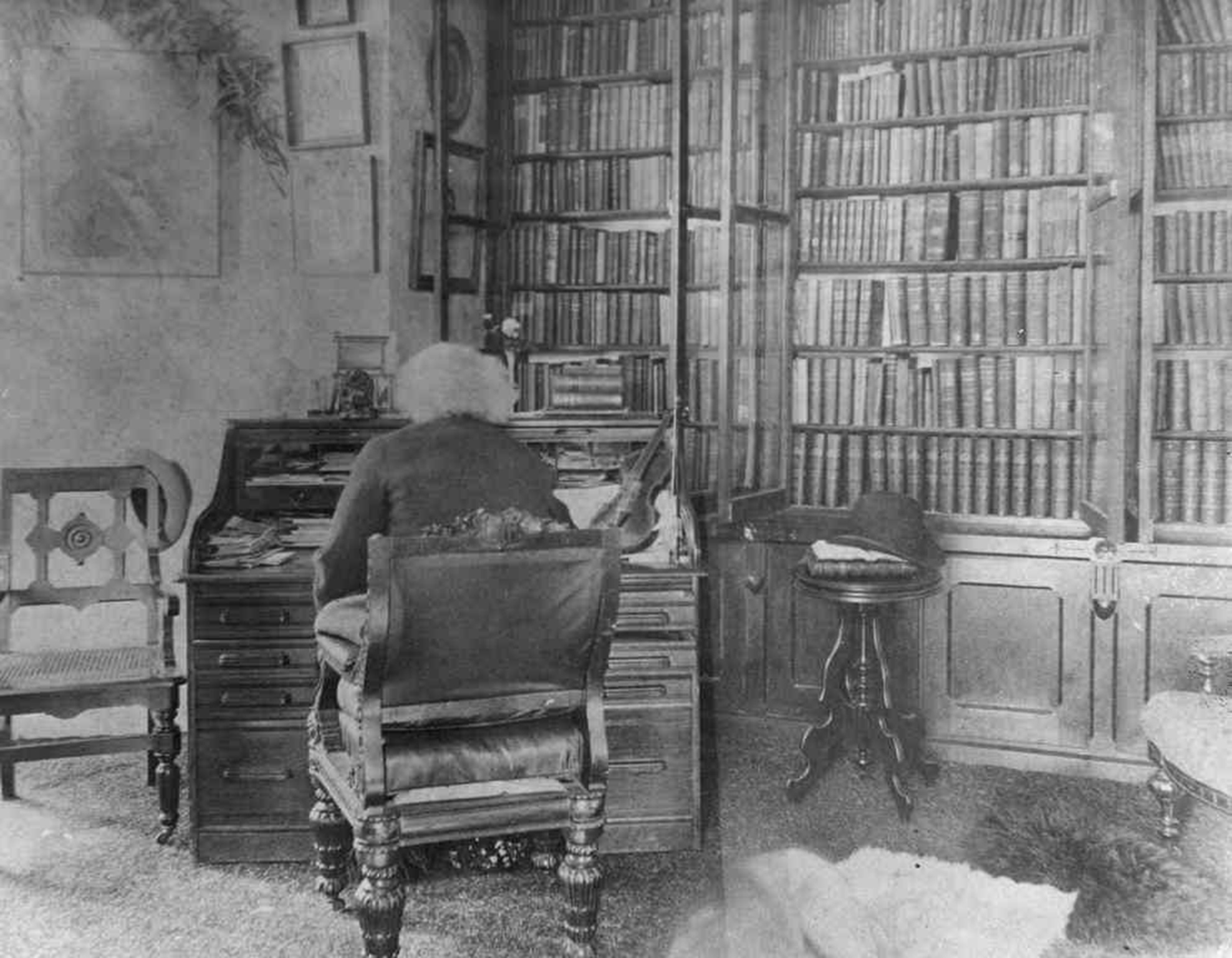

Frederick and Anna had married in New York on September 15, 1838, the day before they arrived in this abolitionist haven. Because his only trained skill was ship-caulking, they needed a coastal town. Along with nearby Nantucket, New Bedford was the center of the first international industry in which the United States dominated: whaling. Ships from all over the world brought a forest of masts to the wharves. Douglass found work immediately — stowing whale oil, shoveling coal, and operating the bellows at a brass foundry. Even while tending this fire, his urge to learn triumphed. “Here I often nailed a newspaper to the post near my bellows,” he recalled later, “and read while I was performing the up and down motion of the heavy beam by which the bellows was inflated and discharged.”

The newlyweds joined the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, held in a schoolhouse on Second Street, three blocks up from the wharves. There, Douglass became sexton and clerk, and in 1839 he was licensed to preach. As would Martin Luther King Jr. more than a century later, Douglass developed his voice in the Black church. “It was a laboratory for the formation of the identity of a New World African people,” Harvard scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr. remarked in a recent PBS NewsHour interview. “After all, there were 50 ethnic groups represented in the slave trade from Africa to North America, and they had to forge and form into one new people, the first truly pan-African people.”

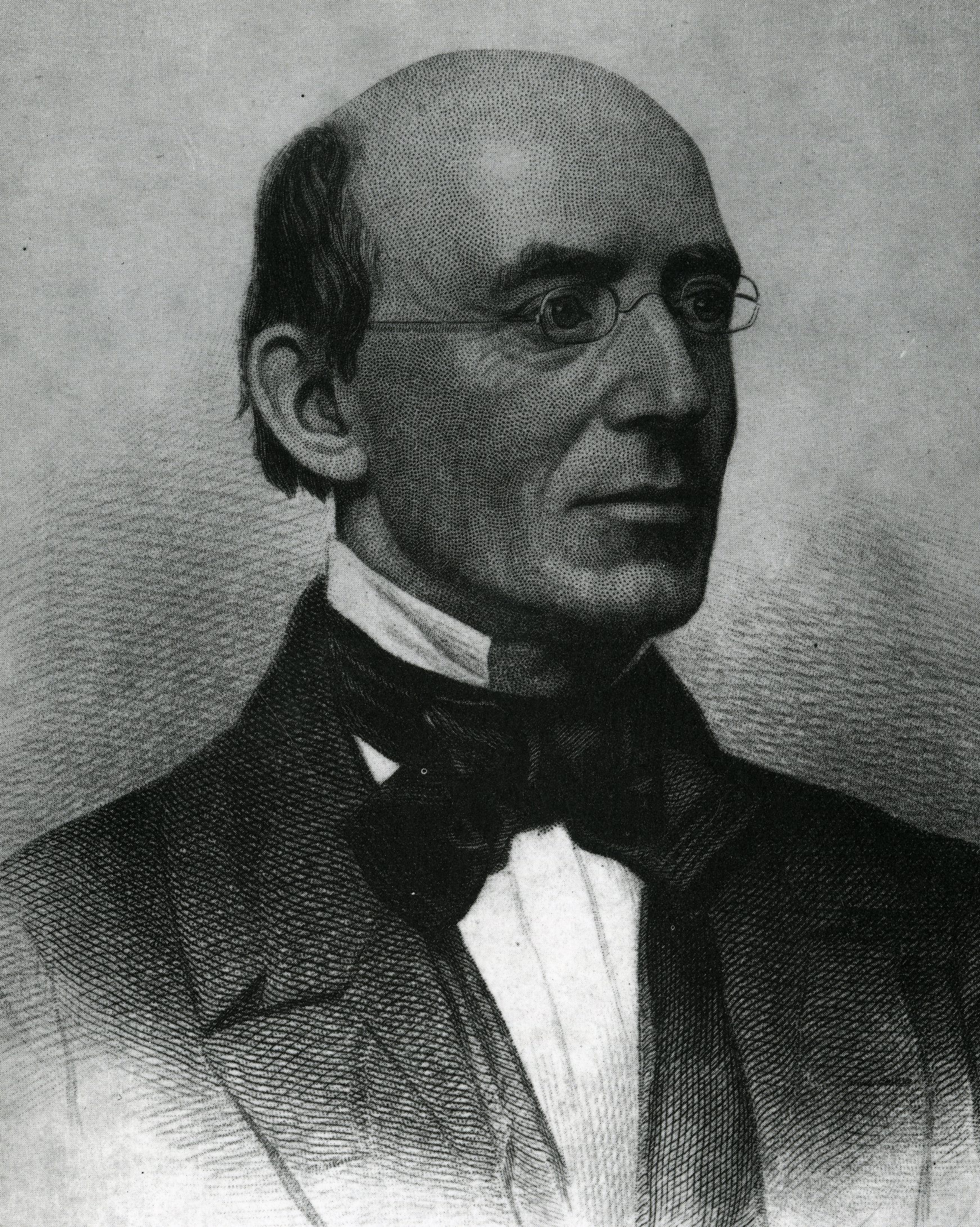

Then Douglass encountered The Liberator, an influential — and to slaveholders, infamous — antislavery weekly. Religious rather than political in tone, it preached for immediate, total abolition. Published in Boston, edited by white activist firebrand William Lloyd Garrison, The Liberator ran pieces by a number of Black activists and writers. “The paper became my meat and my drink,” Douglass recalled. “My soul was set all on fire.”

He attended many antislavery rallies, including a lecture by Garrison himself. “My acquaintance with the movement increased my hope for the ultimate freedom of my race,” Douglass wrote, “and I united with it from a sense of delight, as well as duty.”

By 1841, white abolitionists were talking about trying to purchase Douglass’s freedom. He attended a major mixed-race rally beginning August 11 in the handsome Nantucket Atheneum. Other attendees included Massachusetts astronomer Maria Mitchell, the first female scientist widely recognized in the United States, and the formerly enslaved Isabella Baumfree, who would later rename herself Sojourner Truth. Garrison’s colleague William C. Coffin, a Nantucket banker and ardent abolitionist, had heard Douglass speak at the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church in New Bedford during the spring. When he saw Douglass in the crowd, Coffin invited the 23-year-old to speak.

![“The [abolitionist] paper became my meat and my drink,” Frederick Douglass wrote of The Liberator. “My soul was set all on fire.”](https://cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/bostonglobe/CPSKPP5TWBCBTPKBP7T6ZVU5BQ.jpg)

Douglass was asked to talk about his experiences growing up in slavery. Hesitating, he stepped forward. “I felt myself a slave,” he wrote later, “and the idea of speaking to white people weighed me down.” Onstage before hundreds of people, at first he trembled and stammered, apologizing for his ignorance and declaring slavery “a poor school for the human intellect and heart,” as Garrison later noted. But after only a few minutes, Douglass began to relax.

The crowd was “completely taken by surprise,” Garrison reported. Throughout, they had interrupted with thunderous applause. When Douglass walked offstage, Garrison, who said that he was “filled with hope and admiration,” rose and declared that not even Patrick Henry had spoken more eloquently about liberty than this fugitive from slavery. He reminded the crowd of the dangers that this young man faced “even in Massachusetts, on the soil of the Pilgrim Fathers.” He asked whether they would “allow him to be carried back into slavery — law or no law, Constitution or no Constitution.”

“No!” they roared.

“Will you succor and protect him as a brother-man — a resident of the old Bay State?”

“Yes!”

No known transcribed accounts exist of Douglass’s speech that day, but the text of a talk he delivered in Lynn in early October survives. It fits descriptions by witnesses of his impromptu remarks in Nantucket. At that gathering in Lynn, he spoke of having “suffered under the lash without the power of resisting.” He reported with sorrow that the man who had kept him enslaved in Maryland was a leader in the local Methodist Church whom he’d witnessed tying the hands of one of the young enslaved women and lashing her already-scarred back as she screamed.

At age 6, on the day his grandmother delivered him to the plantation house to begin a life of bondage, Douglass had witnessed his 15-year-old aunt being whipped by their white slave-owner for showing romantic interest in an enslaved man her own age, rather than in him. A few years later, Douglass would open his first book with this horrific memory, making it clear that cruelty was not an aberration in slavery: The institution was founded upon unpunished rape, torture, and murder.

After the impromptu Atheneum speech, Garrison begged Douglass to join the organized antislavery cause. Douglass was astonished. He said that he was young and inexperienced, not equal to such a task. He worried that his joining the association might even hinder the cause and that public appearances might draw slave-hunters.

Garrison and his colleagues persisted. And they were persuasive. Douglass didn’t return from Nantucket to operate the bellows at the New Bedford brass foundry. He rolled no more barrels of whale oil. Someone else would shovel coal for white people. Instead, he accepted the invitation to fight the national evil that had left millions without family, law, or safety in the land where they lived through no choice on their part.

Leaving at home his devoted and resourceful wife, Anna, who had helped make this new world available to him, he took to the road with visionary haters of slavery. They were pelted with rotten eggs in Indiana, where white bigots attacked them and left Douglass unconscious and with a broken hand. Violence and threats became part of their daily lives. Douglass finally fled to Ireland and Great Britain, staying for 21 months until English friends paid for his freedom.

Wearying of extempore accounts of his own life, Douglass quickly moved from speaking to writing — speeches, articles, and books. His eloquence led detractors to dismiss him as an educated actor. Four years after the Nantucket rally, his first autobiography was published: Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave, Written by Himself, in part to counter skeptics. “One of the most efficient advocates of the slave population, now before the public,” Garrison wrote in a preface, “is a fugitive slave.”

George Lewis Ruffin, a judge and legislator and the first Black man to graduate from Harvard Law School, wrote the introduction for a revised edition of Douglass’s third autobiography, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, published in 1892. Of the man who had tended the foundry bellows in New Bedford, whose soul had been “set all on fire” by the abolition movement, Ruffin wrote, “The most striking feature of Douglass’ oratory is his fire, not the quick and flashy kind, but the steady and intense kind.”

Today, with many white Americans striving to make voting more difficult for their Black neighbors, Douglass’s moral authority rings across time. In the summer of 2020, a century and a quarter after his death, amid international protests against the kind of police violence that resulted in the murder of George Floyd, NPR invited a number of Douglass’s young descendants to join in reading together his famous 1852 speech, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”

This group reading was a deeply moving reminder of Douglass’s power as a writer and as a moral leader. Douglass addressed his speech to white America: “Are the great principles of political freedom and of natural justice, embodied in that Declaration of Independence, extended to us?” His words still resonate: “There are seventy-two crimes in the State of Virginia which, if committed by a Black man (no matter how ignorant he be), subject him to the punishment of death; while only two of the same crimes will subject a white man to the like punishment.”

A masterful writer, Douglass made himself symbolic, as did his contemporary Henry David Thoreau. Trained as a preacher, Douglass took his own experience as the starting verse for his eloquent sermons, but made it representative of millions of other American lives. His loss of his mother, his cruel and absent father, the lash on his back, became theirs. And his triumph also became theirs.

Michael Sims’s books include “The Adventures of Henry Thoreau” and “Arthur and Sherlock.” Send comments to [email protected].