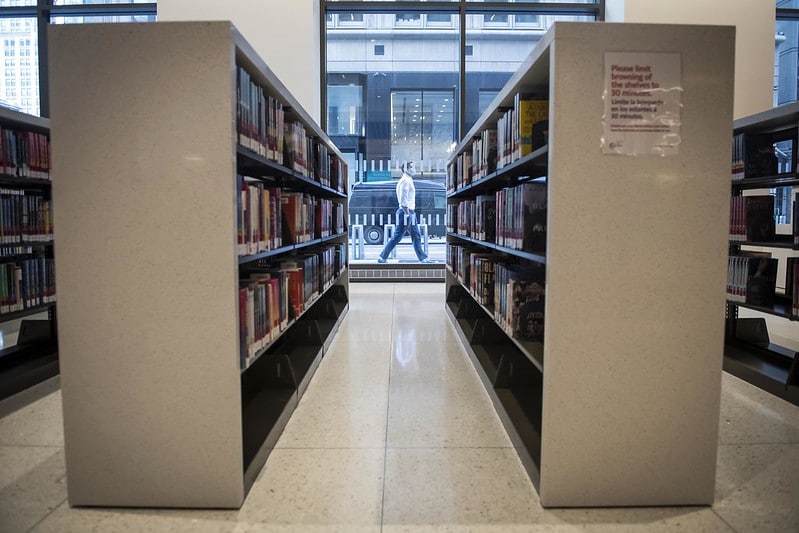

Reading New York (Photo: Ed Reed / Mayoral Photography Office)

Another school year has passed, the most unusual I can remember. Forced into distance learning by the pandemic, I never met any of my students. All I could see were twenty-four curious and worried faces in little squares on the computer screen. Even so, they were there, fully engaged in our journey through the history, politics, and government of New York City, trying to get a better grip on the city that has been a destination for the American Dream for generations.

My Hunter College students bring their own life experiences to our conversations: immigrants, migrants and locals; Black, brown and white; LBGTQ and not; often challenged economically, rarely privileged. You know New York; they are New York. This is CUNY.

So where could we start this conversation? Is New York a place or an idea? A goal or an illusion? Does it have a special meaning or purpose? Or is it different things for different people? How does this complex metropolis fit together? Does this creature called Gotham have a soul? If so, is it a kind and generous soul who cares for those who are struggling? Or does it have a mean and competitive attitude that accepts the harsh notion that only the “strongest” will survive?

All were relevant questions as the city neared one of the most momentous elections in history. Could the outcome of this election tell us anything about the soul of New York? Are his instincts friendlier or meaner?

Before getting into the usual academic material, we began our journey with a literary route. New York has drawn the attention of many great writers. Because of their special gifts, they see things more clearly than the rest of us, often sooner, and then explain them in a way that is memorable.

We started with Italo Calvino. Calvino (1972) draws pictures with words. He presents the idea of the city in several dimensions: as physical structures made of bricks and mortar, as networks of complicated relationships between people, as storehouses of traditions and memories that carry us on. Each one, he reminds us, is just a passing visitor. While one might hope to influence direction, the city is a complex organism with an ever-changing mind and dynamic of its own. How humiliating!

Writing in 1968, Joan Didion recalls the life of a 22-year-old who came from California to a city of endless opportunity, certain that “something extraordinary was about to happen,” and seemed confident it would happen to her. Full of youthful energy, she is determined to explore the city all by herself, without contacting her father, who would surely send her a check to help if things get difficult. Junot Diaz (2000) would never have considered doing this with his father. The elder Diaz had arrived in Nuova York from the Dominican Republic only to find that he couldn’t afford to live here. When Junot arrived college educated at the age of 26, he had no choice but to conquer the city, whose skyline looked like “science fiction,” with only his own limited resources.

An optimistic EB White (1949) insisted that it is the “settlers” who give New York his passion, because “everyone embraces New York with the intense excitement of first love, everyone sees New York with the fresh eyes of an adventurer “. He continues: “The city is like poetry: it compresses all life, all races and races into a small island and adds music and the accompaniment of internal motors.” White described neighborhoods with their grocery stores, saloons and barbershops as “self-sufficient” Communities that give meaning to everyday life, cocoons of comfort that protect one from the cold anonymity of a big city existence. Maybe he had never met a Diaz before.

Nor a Jean Kwok (2012), who tells the story of a Chinese immigrant mother who works in a sweat shop for days while unsuccessfully struggling through New York’s cultural landscape for her talented daughter. The more her daughter assimilates through the world of dance, the more she distances herself from her loving mother. Can there be a higher price to become a full-fledged New Yorker? Such a pain is out of sight for those who have never done this long immigration journey.

John Steinbeck (1943) recalls two entries in the city. The first time here, after graduating from Stanford, he made decent money doing “cement rolls” in a construction job he found through family contact before another relative got him a spot in a local newspaper about stories in Brooklyn and Queens reported. Journalism didn’t do him any good. He knew little about newspaper writing and was fired. After his girlfriend left him for a banker, he left the “cold and heartless” city and returned to California as a defeated young man. As he put it, the city “beat my pants off”.

Steinbeck’s “second attack on New York” was “different, but just as ridiculous as the first”. He had just won a Pulitzer Prize for The Grapes of Wrath and was signed to Paramount Pictures for Tortilla Flat. He now lived in an Upper East Side townhouse with a private garden. When he got to know the local butcher, newsagents and liquor sellers, “everything was fine”. His neighborhood became his village, just as White had envisioned it, and things that might have annoyed him the first time suddenly became part of New York’s charms.

James Baldwin (1960) also remembers the role of the shopkeeper in Harlem of his childhood. Those who survived economically lent their customers when people had no money – not that the grocers had much choice. Instead of offering comfort, Baldwin writes with bitterness about his segregated community in which residents felt trapped. He describes the “hideous projects” as “colorless, bleak, tall and repulsive”. For him “they provide proof of how thoroughly the white world despises its black inhabitants”. No signs of privilege here. No family with money or connections. As black, gay and poor, as he put it, he had reached the “Trifecta”. Baldwin writes with conviction and does not resort to exaggeration because he knows it is not necessary. He tells of police violence and the hostility between citizens and officials as if he were writing today.

Baldwin’s Harlem roommate, Langston Hughes (1951), foresaw that tension would eventually “explode like a raisin in the sun.” In the mid-1960s, that collective frustration exploded with rioting in cities across the country, as it did in less violent forms last summer following the assassination of George Floyd.

Did these authors all write about the same city? Well yes and no. They all lived in New York, but in very different places. As they write at different times, their observations are timeless. New York is full of conflict, tension and injustice. Depending on what is yours, life in New York can be an adventure or a struggle. But which part of it reveals the real soul of the city?

Many of my students are familiar with the wisdom of Jane Jacobs and find the soul of the city on the neighborhood sidewalks where people interact. They will tell you that the physical city, with its corporate offices, luxurious skyscrapers and dilapidated walk-ups, reveals the essence of New York. You are aware of the contradictions. You want to believe that friendlier instincts will eventually rule, but aren’t sure if that will happen.

In search of further answers, we turned to politics as a reference to the instincts that can prevail. Over the years, New York City has had some formidable personalities taking on the role of chairman of the board. At different times they have represented the collective spirit of the city with its fears and aspirations – or at least the mood of those who vote or participate in its verbose political life. This is where the priorities are set. Here it is decided who wins and who loses.

This is part one of a two-part reflection. Read part two about politics, leadership and mayors of New York City here.

***

Joseph P. Viteritti is the Thomas Hunter Professor of Public Policy at Hunter College. His recent books on New York include The Pragmatist: Bill de Blasio’s Quest to Save the Soul of New York and Summer in the City: John Lindsay, New York and the American Dream.

***

Do you have an idea or a contribution to the Gotham Gazette? E-mail This email address is being protected from spam bots! You need JavaScript enabled to view it.