Lucinda Williams covers Joe South’s “Games People Play” on her recently released album “Southern Soul: From Memphis to Muscle Shoals and More.”

It’s a very good cover, not surprising given Williams’ pedigree and her sense of history and place. The 1968 original is a startling record, modern-sounding if you disregard the “sock it to you” reference. I remember the South version best, but some remember it by Freddie Weller, who played lead guitar in Paul Revere and the Raiders while moonlighting as a country singer.

In another example of the Mandela effect — the phenomenon of mass misremembering, like when people incorrectly recall that Nelson Mandela died in prison in the 1980s or that the Warner Brothers’ cartoon series was “Looney Toons” rather than the correct “Looney Tunes” — Weller did record the song and have a hit with it shortly after South recorded it and had a hit with it.

The difference was that South’s version was on the pop charts, reaching No. 12 on the Billboard Hot 100 in 1968, while Weller got to No. 2 on the country charts in 1969. What version you remember likely has to do with what radio station you listened to at the time; my parents mainly tuned to country radio while I listened to pop, so I got whipsawed between the two versions and remember being confused by their sounding alike but definitely not the same.

While the two versions differ in significant ways, they share some DNA. Weller and South had played together as teenagers on a radio show called “The Georgia Jubilee” — which also featured a piano player named Ray Stevens (nee Ragsdale) and another guitarist named Jerry Reed — and had collaborated in the studio on dozens of recordings.

Weller had for a time played guitar in South’s band. They had worked together on “Down in the Boondocks,” a record South wrote and produced for Billy Joe Royal (another Georgia Jubilee alumnus) which reached No. 9 on the Billboard Hot 100 in 1965 and which Weller dutifully covered in 1969 and took to No. 25 on the country charts.

After Royal scored his hit, he went out on the road. He didn’t have a full band but relied on Weller to recruit musicians at each tour stop and teach them the songs.

I prefer South’s version to Weller’s if only because of the exotic Danelectro electric sitar intro that South played (though Freddy’s version features the excellent Red Rhodes on pedal steel guitar). And South’s sinewy baritone is a more distinctive instrument than Weller’s tenor. But those are matters of taste about which reasonable people can disagree.

Williams’ version falls into the respectful-but-not-slavishly-so category, with her distinctive phrasing and earth-mother snarl (she attacks — and sells — the “sock-it-to-you” line with earnest ferocity) immediately staking a claim on the track.

She’s not going for a definitive version, but a down-and-dirty live-in-the-studio take, part of the series of six livestream concerts she performed in 2020 as a way to finesse the pandemic.

Those shows, mostly full-band performances recorded live at Ray Kennedy’s Room and Board Studio in Nashville, were comprised of a themed set of cover songs curated by Williams; a portion of the ticket sales went to support independent music venues struggling in the wake of covid-related shutdowns.

“Southern Soul: From Memphis to Muscle Shoals and More” is the second of these shows to be released on CD and to digital retailers (though apparently not to streaming services) after last year’s “Running Down a Dream: A Tribute to Tom Petty,” which saw Williams and her band bashing through a set of Petty covers.

She also recorded a set of Bob Dylan covers, a series of ’60s country covers, a Rolling Stones show, and a slate of Christmas songs. All are available for purchase in various formats at lucindawilliams.com, with downloads immediately available.)

Lucinda Williams’ album “Southern Soul: From Memphis to Muscle Shoals and More” features a cover of Joe South’s “Games People Play.”

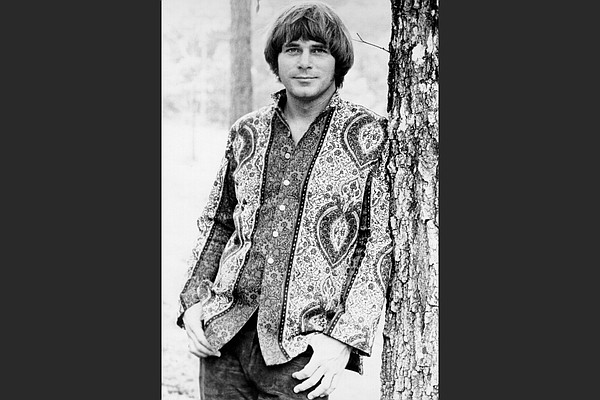

Joe South — real name Souter — was an active cat.

A lot of people might think of him as a one-hit wonder, but the truth is he had a couple of other notable hits, “Don’t It Make You Want to Go Home” later in 1969 and “Walk a Mile in My Shoes” in 1970. Both were probably eclipsed in the public imagination by the Elvis Presley cover versions. Brook Benton also recorded the former.

South played bass on Bob Dylan’s “Blonde on Blonde” album. He played lead guitar on his boyhood pal Tommy Roe’s “Sheila.” That little tremolo guitar figure that kicks off Aretha Franklin’s “Chain of Fools”? Yeah, that’s South.

The Deep Purple song “Hush”? South wrote that.

As mentioned earlier, South was on the “Georgia Jubilee” as a teenager, a show hosted by Bill Lowery, an Atlanta-area talent scout, record label owner and all-around entrepreneur. Lowery not only hosted the “Georgia Jubilee” but founded the ambitiously titled National Recording Corporation, for which South (and Weller, Stevens, Reed and a young Mac Davis) all worked before the label folded in 1961.

South was employed as a producer and guitarist but also recorded music for NRC. In 1958, after Elvis went into the army and rock ‘n’ roll foundered on the shoals of self-parody (hits that year included television horror host John Zacherle’s “Dinner with Drac,” the Royal Teens”https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2021/aug/08/southern-soul-williams-pays-props-to-joe-south/”Short Shorts,” and the Chordettes”https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2021/aug/08/southern-soul-williams-pays-props-to-joe-south/”Lollipop”), South released a single called “The Purple People Eater Meets the Witch Doctor” written by Gordon Ritter, a nephew of the famous Tex, and J.P. Richardson, a Beaumont, Texas, disc jockey better known as The Big Bopper.

Richardson had already tried (and failed) to make it as a country crooner, and it’s fair to say that he wrote “The Purple People Eater Meets the Witch Doctor” as an attempt to cash in on one of the most obnoxious pop music fads ever.

A songwriter named Ross Bagdasarian, recording as David Seville, had discovered recording his normal voice at half-speed and playing it back a full speed resulted in a high-pitched “chipmunk” effect. He exploited this gimmick in “Witch Doctor,” released on April Fool’s Day 1958, which immediately shot to No. 1 on the Billboard Charts. (It was the No. 4 song for the entire year.)

A month later, Sheb Wooley, at the time known as a character actor, released his song “The Purple People Eater,” which also contained a sped-up vocal, though it wasn’t quite as high-pitched as the one in “Witch Doctor.”https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2021/aug/08/southern-soul-williams-pays-props-to-joe-south/”Purple People Eater” also contained a toy saxophone break that had been similarly processed.

(To be pedantic about the squeaky vocal craze, one notes that the sped-up voices were often referred to as the “Pinky and Perky effect,” referring to a BBC television program about two anthropomorphic puppet pigs whose voices were created by replaying original voice recordings at twice the original recorded speed. Pinky and Perky also sang versions of current popular songs. We will leave it to more-informed and interested parties to decide whether or not Seville/Bagdasarian copped Pinky and Perky’s act when he created Alvin and the Chipmunks.)

Richardson had recorded the song himself first, and thought it might be the hit he needed to jump-start his career as a rock ‘n’ roll performer. It didn’t. But the flip side, “Chantilly Lace,” took off, leading to Richardson’s touring with Buddy Holly and eventually putting Richardson in that small plane with Buddy Holly and Richie Valens on the Day the Music Died.

“The Purple People Eater Meets the Witch Doctor” didn’t do much for South’s career either, though some sources credit it as a minor hit. But the next year Gene Vincent recorded two songs South had written. After NRC went under, South moved on to Muscle Shoals and Nashville, a peripatetic guitar man. He and Glen Campbell did a lot of the guitar work on the second and third Simon and Garfunkel albums.

Then, in 1964, South enlisted his friend Royal to record “Down in the Boondocks.” They recorded it in Atlanta on a three-track machine that was hardly state of the art even then, using a septic tank as an echo chamber. Despite the primitive engineering, the record somehow worked, though South maintained he’d never intended for it to be released. He’d simply wanted to cut a demo record to present to Gene Pitney. South was trying to re-create the atmosphere of Pitney’s evocative 1963 hit “Twenty-Four Hours from Tulsa.”

Royal remembered it differently; he said they never had any real hope of getting the record to Pitney. He said he sang it in Pitney’s style in an attempt to fool the audience into thinking it was a Pitney record. (Like the strategy exploited by Canadian band Klaatu in the mid-1970s, when its members went to some lengths not to dissuade listeners from believing their debut album was actually made by the secretly reunited Beatles recording under a pseudonym.)

In any case, it took a while, but Royal’s version went Top 10 in 1965, and he went on to record five more of South’s songs over the years. Then in 1969, he wrote and recorded “Games People Play,” a work of aural social criticism allegedly inspired by a book by psychiatrist Eric Berne.

Berne’s book was all about transactional analysis, and popularized a post-Freudian psychoanalytic theory that looked at the “ego state” of an individual to understand and remediate emotional problems.

It was assigned reading in some high schools in the ’70s, which seems extremely strange now.

It postulated that everyone had three ego states — parent, adult and child — and that there were four life positions a person could hold, the healthiest being “I’m OK, you’re OK.”

If South was indeed inspired by Berne’s book, lyrically he didn’t get too deep into the weeds of transactional analysis. He simply called out hung-up hypocrites, self-destructive pathologies and Aquarian New Age jargon.

“Games People Play” is a oblique take-down song worthy of Tom T. Hall, with a major key melody that practically sings itself:

- People walkin’ up to ya

- Singing “Glory Hallelujah”

- And they’re tryin’ to sock it to you

- In the name of the Lord

- They’re gonna teach you how to meditate

- Read your horoscope, cheat your fate

- And furthermore to hell with hate

- Come on and get on board …

It was Joe South’s finest moment.

It won the Grammy Award for Best Contemporary Song and the Grammy Award for Song of the Year. And Joe South was rarely heard from again. It’s a dirty rotten shame.

If you can find a copy of South’s debut album, originally called “Introspect” (and one great thing about the digital age is that you can find it without looking all that hard — it’s been released to Spotify and other streaming services) and listen to it, you might be amazed. It’s a crazy jam.

It might be the first country-soul record, and certainly serves as a template for the Elvis Presley and Tony Joe White records that would soon follow, though South was far more inventive and musically ambitious than those two artists.

Listening to South’s version of his composition “Rose Garden,” which would become a massive hit for Lynn Anderson in 1971 (and had been previously recorded by Royal in 1967 as “I Never Promised You a Rose Garden”) you’ll hear it punctuated by what sounds like a cracking egg. The players on the album are almost progressive rockishly virtuosic, and there’s that electric sitar. The songwriting — and the singing — is so good.

Capitol didn’t have much faith in the album though, and it almost let it go out of print when “Games People Play” started making it up the charts. Then it pulled all copies of the album, re-sequenced the tracks and re-issued it with the new title “Games People Play.” Didn’t help much; the album peaked at No. 117.

South apparently didn’t help himself; there are stories about him not showing up for recording sessions and in his later years he admitted that he started doing drugs not so much for recreation but to try to find inspiration.

He was never a natural live performer and often got confrontational with concert audiences. Then his brother, the drummer in his band, committed suicide in 1971, and South took some time off, repairing to Maui to live in the jungle and do drugs.

When he tried to come back he was a prickly mess, as evidenced by his notorious “I’m a Star,” which was on his dark (and sometimes brilliant) would-be comeback album “A Look Inside” from 1972:

- If I make one mistake, you’ll hear it on the news

- Well, I’m only human and God knows I really paid my dues

- Just bein’ the human race

- And to run this frantic pace

- Requires enough amphetamine to blow a fuse

And on “Imitation of Living,” South sang:

- Too many bills that

- I forgot about

- And there’s too many pills I just can’t make it without

- Whoa, I make a lot of money, but I throw it all away

- To the dude that deals the dope

- ‘Cause that’s my only hope

South reportedly wanted Lynn Anderson to record “Imitation of Living.” Maybe that’s an indication of how far gone he was at the time.

He kicked around for years, recording sporadically, finally getting clean and moving into music publishing. The L.A. Times’ Robert Hilburn published a remarkably candid interview with him in 1994, in which South credited his second wife for getting him off pills and saving his life.

He told Hilburn that when he won his Grammy for “Games People Play,” he “staggered up and sort of leaned against the mic and said something, but I don’t even remember — the drugs had taken over.”

His wife died in 1999, and South cycled through relapses and recoveries, with occasional attempts at returning to performing, until he succumbed to heart failure in 2012. The last song he wrote and recorded was called “Oprah Cried,” about a fictional encounter on the Oprah Winfrey show in which the host gets him to open up about his private life.

- Oprah cried

- She said “Son, I thought I’d heard it all”

- Tears runnin’ down her makeup

- I thought she was gonna break up

- As I told about the things I swore I’d always hide

I don’t know why Lucinda Williams chose to record “Games People Play.” Perhaps as a top-flight songwriter herself, she recognizes a great song when she hears one. But I like to think that she knows Joe South’s story too, and that his story might resonate with her. He was another of what Leonard Cohen called “workers in song,” popularly taken as a one-hit wonder.

Email: [email protected]