Staples goes first, alone and great. Jackson follows her with equal strength and despite everything that has tormented her. Then together – Jackson radiant in a fuchsia dress with a gold diamond under her chest; Clamps in something short, lace, belt and white – they embark on the most amazing duet I’ve ever heard, seen or felt. They share the microphone. You pass it on between you. Howling, moaning, whining, jumping, but within the generous contours of the song and somehow under control. My tears weren’t waxed as I watched. The canals just gave way, and the mask I was wearing in the theater where I was sitting was eventually covered in liquid, viscous salt.

They sing for the festival visitors. They mourn all deaths – of leaders, followers, troops and civilians. You are lamenting, if you will put it that way, a generation transition from one phase of black political expression to another, from determination to anger, from the splendor of Jackson’s tufts of hair to Staples’ blunt afro. They sing this cherished classic of mourning to mourn the present and the past. If you hear them now, in the summer of 2021, sound out the earth and scratch the sky, you cry, not only because of the raw beauty of their voices, but because it feels as if these two instruments of God are also mourning the future.

I don’t remember how long this performance lasts. It doesn’t even have an ending, per se. It just ends with every woman returning to Reverend Jackson, into the band. But when it’s over you don’t know what to do – well, except never forget it. It is an extraordinary event not only in music history. It’s a mind-blowing moment in American history. And for five decades the recordings of it apparently just lay in a basement, waiting for someone like Thompson to give it its place.

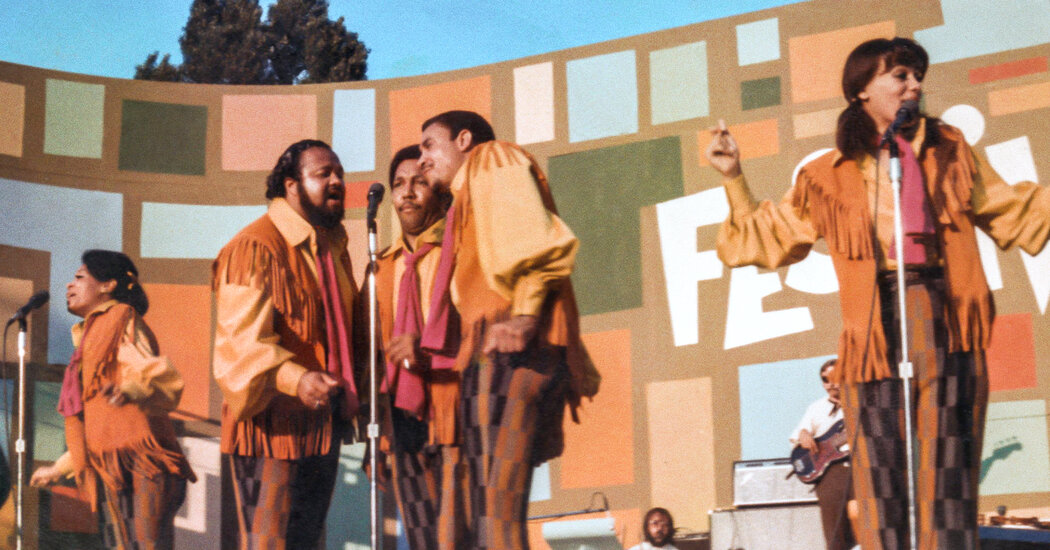

The whole film is chargeable. It’s true that nothing matches Mahalia Jackson and Mavis Staples high. But nothing around them feels puny or like an afterthought. Thompson has an assortment of people looking at footage from the festival – attendees who were kids and teenagers at the time, artists who were there, people like Sheila E. who learned their craft from some of those artists. And I was almost as devastated when Marilyn McCoo put her hands over her face as she watched her younger self with the rest of the Fifth Dimension and shared how they felt in between as black artists who blacks didn’t always think were black enough. Their sound was light and round, based on strings and harmonies that were commercial but not cool for 1969. In this film, the fifth dimension between Simone and Max Roach and Hugh Masekela in no way looks like an outsider. You seem like a family.

During this matter, Thompson drops explanatory information and montages that are thwarted with more information. For example, a passage about the national climate of ’69 is mixed in with the Chambers Brothers’ festival appearance. And you sit there in awe that the movie hasn’t lost you. It has its own rhythm. The pictures, the music, the news, the memories, the commentary often come across to you all at once. And with another director all that remains is noise, chaos. Thompson is certainly a band leader here – a band leading drummer; a band-leading drummer who hangs up – important. The rush works differently here. The chaos is an idea.

On the one hand, it’s just cinema. On the flip side, the editing has something to do with the music, the way the talking enhances what is happening on stage rather than enhancing it. In many of these passages, facts, twists, jive and comedy intersect and yet in balance. So yes: cinema, of course. But also something that feels less common: syncope.