Besides The Roots and her nightly appearance on The Tonight Show with Jimmy Fallon, Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson has many other jobs.

“Usually I jump into the ignorant lake of creativity with absolute devotion,” says the drummer, A-list DJ and podcast host of Questlove Supreme.

“Write a book? I’ll do this. Teach at NYU? Yeah, I’ll do that. Anything I’ve done in the food world [including his Questlove’s Potluck shows and plant-based Questlove’s Cheesesteaks]. Everything that is outside of my comfort zone of playing drums. “

But when the opportunity arose to take responsibility for what was to become the Summer of Soul (… or if the revolution couldn’t be televised), his cheerful and insightful documentary about the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival was he’s not so sure.

“When I was directing a movie, I was something like … [making a screeching sound, slamming on the brakes]”, He said last week via Zoom about the film, which is referred to as” Questlove Jawn “and won both the Grand Jury Prize and the Audience Prize at this year’s Sundance Film Festival.

It opens in theaters (where it’s most valued) and on Hulu on July 2nd, and will be shown in the Philadelphia Film Society’s Drive-In Theater in Navy Yard on Monday as part of the Welcome America celebration.

“I don’t know if I can jump off this cliff folks,” he recalls. “I tried to find my way out. Why can’t I just be Executive Producer and Talking Head? “

Of course, Questlove has first-hand music festival know-how: He staged Philadelphia’s Roots Picnic with the co-leader of the band Black Thought for 12 years in a row before it was canceled in 2020 due to COVID-19.

This year, he said, with the concert industry coming back to life, the band had hoped to host an October picnic at the Mann Center but would reluctantly have to take a pass. “The Roots Picnic will not take place in 2021,” he said. “But we’re coming in 2022!”

Questlove served as the music consultant and voice actor for the Pixar film Soul last year, but hesitated to add “film director” to his list of professions, in part because of the size of the job ahead. Summer of Soul brings to life a glorious black music event so dazzling in presentation and scope that its deletion from historical records has been insane for half a century.

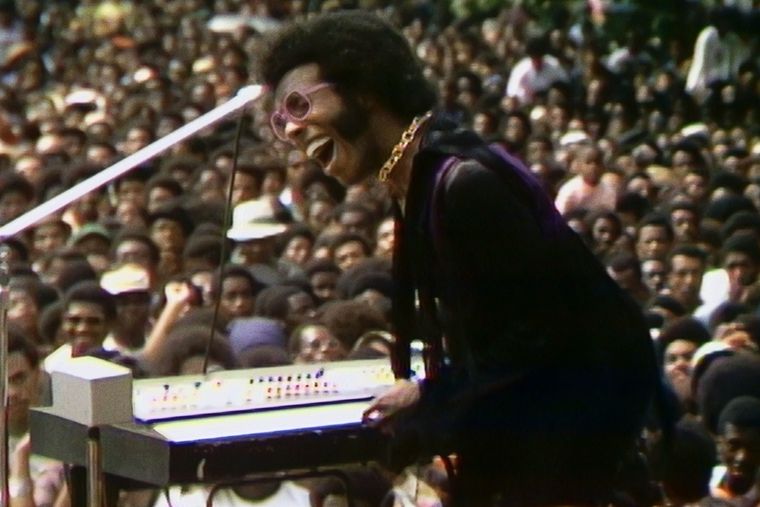

In a series of free concerts held on Sundays at Harlems Mount Morris Park (now Marcus Garvey Park) from June to August 1969, over 300,000 people saw glowing performances by Sly and the Family Stone, Stevie Wonder, Nina Simone, BB King, Gladys Knight & the Pips, Hugh Masekela, the Chambers Brothers, the Fifth Dimension, the Staple Singers, and more.

Staged the turbulent year after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. – the year “when the ‘Negro’ died and ‘Black’ was born,” says an offscreen voice in the film – the festival was a celebration of black culture for a lively generation group of people, sporty dashikis and afros. The Black Panther Party supported security. Jesse Jackson delivered an “I am Black, I am Beautiful!” Sermon and introduced Mahalia Jackson and Mavis Staples, who sang “Precious Lord, Take My Hand,” King’s favorite song.

Veteran television producer Hal Tulchin filmed the entire festival, which was broadcast in hour-long clips on late-night New York television. He then tried for decades to sell it as “The Black Woodstock” to network TV managers or as a documentary film.

There were no buyers. For nearly 50 years, 40 hours of tapes lay in Tulchin’s garage before Questlove was approached in 2017, the year Tulchin died at the age of 90.

Producers David Dinerstein and Robert Fyvolent told Questlove – who taught Prince 101 at New York University and whose fifth book, Music Is History, is due out in October – that he would be the ideal music nerd to make the film.

“They said, ‘If you ever get into this medium, this is the perfect stepping stone,'” he said. “I just had to overcome myself and my fears.”

»READ MORE: Roots Picnic packs into a crowd for the first time at the Mann Center

However, despite his encyclopedic knowledge, Questlove had never heard of the Harlem Festival. “I live in this world where Biz Markie calls you and says, ‘I have this 45 that you don’t have!’ Hip-hop producers trying to outdo each other. So immediately my ego was, ‘This didn’t happen because I would have known.’ ”

He soon realized that not only was the festival real, but he had seen some of the extremely rare recordings. “In 1997, when The Roots first came to Japan, my translator took me to a place weirdly called the Soul Train Cafe.” TV monitors showed bootleg clips of what he now recognized as Sly Stone’s appearance on the HCF.

The exciting performance material like Stone’s – or as breathtaking as Stevie Wonder’s drum solo and David Ruffin’s sing-along on “My Girl”, recorded on the day Apollo 11 landed on the moon – could have been thrown away, is a cultural crime, the Questlove decided to correct.

“I kept making excuses,” he says, noting that many of the festival’s artists, like Wonder and the Staple Singers, had not yet peaked in popularity, which may explain why mainstream America was not interested in one The event had marked a golden era for the achievements of black music.

“But the truth is, whether it’s blatant racism – like, ‘You won’t cross that bridge over the racism of our corpses – or benign racism that’s more dismissive, it doesn’t matter. I say benign racism stings more because it is made so passive-aggressive. “

Summer of Soul does an excellent job of contextual storytelling. Sheila E. illuminates the percussion techniques of Ray Barretto and Mongo Santamaria. Critic Greg Tate becomes eloquent about Pops Staples, Sonny Sharrock and Sly Stone, whom he calls “a proto-prince”.

And perhaps the director’s most fruitful decision for the first time was to show footage to actors like Marilyn McCoo and Billy Davis Jr. of the 5th Dimension and viewers like Musa Jackson, who calls HCF “the ultimate black barbecue.” Many become emotional when a vanished episode from their youth reappears before their eyes.

His need to tell the story of the Harlem Cultural Festival came true, Questlove says, while reading Prince’s posthumous memoir, The Beautiful Ones.

“He talks about that moment when his father took him to the Woodstock movie when he was 11 and how it changed his life. He knew immediately: I will do that. And I was like, ‘Whoa, what if that movie had existed then?’ Think of the millions of other children who could be affected. “

Since the Summer of Soul story was not yet told at the time, “Soul Train is what it replaces as the flag-planting moment of black joy,” says Questlove. “This is the first time you’ve seen black teenagers on TV who aren’t caught up in controversy or civil rights riot, but rather express joy.

“Now we’re just having this conversation about Black Joy. It’s an important part of our history. It’s not just the bloodshed and the pain we’ve endured. There is also a joy factor that we need to include in the narrative that makes us human. Hopefully this film will do that. “